Parenting is tough, human or otherwise. A few weeks ago, a pair of Blue Jays made their nest, woven with a mix of twigs and blue plastic shopping bags, in the tree projecting from the neighbor's yard into our own in bustling Park Slope. The eggs were laid, the chicks hatched, the parents vomited insects into their mouths. All appeared to be well.

What the poor parents didn't realize? That they weren't in the woods, and they'd inadvertently made a home in the midst of screaming children, Park Slope Food Coop carts, parking cars, and stray cats.

Luckily (or not?), they'd also chosen a spot complete with a resident ornithologist and his ambivalent yet animal-loving spouse.

We were prepared to let nature run its course, until the hiccup: teeny tiny Blue Jay fallen from the nest. It was so ridiculously adorable, that I have to break my non-bird photograph vow right away:

I first noticed this when I got home one day to our next-door (Homo sapien) neighbor watching the little hatchling hobble around a water dish he'd put out for it. The neighbor was concerned, but about to leave on a trip, so I volunteered to be a bird foster parent. After a call to the birder-spouse, I put the chick - now named Albertine by our neighbor - into a cardboard box with nesting material, as seen above (note to all you future baby bird-finders: the #1 best thing to do is put the bird back into the nest, but in this case it was unreachable. Also, it's a myth that the parents won't care for it after human hands have touched it).

The biological parents, meanwhile, were NOT thrilled. Keenly aware of my intervention in their child-rearing, they squawked, dive-bombed, and got closer than made me comfortable. Trying to both a) save my face from Blue Jay mutilation and b) interfere as little as possible, Albertine was left in his box on a garbage can, close to the parents and siblings up in the nest.

I was hopeful, but my scientifically-minded and experienced birder-spouse tempered my optimism. He reminded me of the omnipresent dangers in our neighborhood: the stray cat who likes to hang around our backyard, the giant rats that own most parts of New York City, the hawks and falcons that occasionally fly by, even in urban environs.

Albertine survived all of these his first couple nights. He got bigger, grew some feathers, and even could fly up to our window before pathetically falling down again and hobbling around. Mom and Dad were clearly feeding him when we turned our backs (as evidenced by his healthiness and the bird poop all over the sides of the box).

Until, while I was away on a trip, Crazy Bird Lady (CBL) showed up. You know the type - she feeds a thousand pigeons at a time in the park, certain they will starve without her. Well, said Lady stumbled upon our toddling and hopping bird baby one day and got into a huge fight with my birder-spouse.

And herein lies the larger, philosophical question little Albertine poses: what obligation and right do we, as humans, have to intervene in the natural world?

CBL was convinced that her intervention was not only warranted, but absolutely essential. She rushed to the pet store, bought a syringe, and force-fed Albertine water, despite the ornithologist's insistence that baby Blue Jays actually don't drink water. When he told her to leave it alone and that the parents were rearing it, she was absolutely furious. Unconvinced by his scientific training, she wanted to take it immediately to a bird rescue center. An argument ensued, and my spouse was able to craft a compromise that involved taping the cardboard box up high in the tree, Albertine within, closer to the parents.

Sadly, a few days later, Albertine was gone. We're pretty sure CBL chick-napped him. It seems Albertine may have had a sibling that made it, but he didn't leave a name or number, so we can't follow up. The parents have moved on, and the nest lays abandoned.

Was CBL in the wrong? It's easy to have a gut reaction, but harder to decide what our overall role in these instances should be. It's likely that Albertine wouldn't have made it. On a few separate occasions we saw him hopping in the sidewalk, dodging fast-paced and oblivious pedestrians. Kids tried to pet him, much to his and his parent's dismay. The stray cat continues to lurk; we spotted him in the front yard just the other day, close to where Albertine once practiced flying. It's possible that CBL saved Albertine's life...that is, if he didn't die of starvation on the way to the rescue center (baby birds, in their early days, are fed about every 20 minutes).

On the other hand, Blue Jays are far from endangered species. They are well-adapted to urban life, and co-exist comparatively easily with humans and other animals. And, let's face it, if we rounded up all the bird hatchlings in NYC and guaranteed their survival through intensive care, we'd soon have more birds than our natural resources could possibly sustain. We'd also miss a lot of work and school.

This debate extends, of course, far beyond backyard birds. In Kruger National Park in South Africa, for instance, arguments over whether or not to cull elephant populations through carefully managed hunting licenses are frequent: these giant herbivores destroy areas in which they tread, threatening many other plant and animal species as their numbers rise within park boundaries. Thus, it becomes a question of prerogatives: do we aim for conservation of individual lives or biodiversity? Do we accept our already well-established role as meddlers in the natural world and try to turn destroyers into stewards of the Earth?

Or do we teach the next generation to just walk by little squeaking Albertine, since we know that stray cat is probably hungry?

The Reluctant Birder

A somewhat bitter and always ambivalent forum for the significant others of birders.

Monday, July 28, 2014

Saturday, July 12, 2014

The Field Guide to Birders

First of all, my bad: It's been awhile since my first post (ah,

the joys of summer procrastination). I'll aim to make this a monthly

blog - opt for the RSS feed to follow!

In order to properly delve into the topic of birders, we first need to build our birder-watching identification skills. How do you tell the difference between a data-collecting ornithologist and a camera-wielding bird photographer? Can you spot which birder is just there to cross that "lifebird" (a species you've yet to see in your lifetime) off her list and which would stop to observe his hundredth cactus wren? (my own birder falls into the latter category.) Despite the seemingly discrete categories outlined here, the cultural anthropologist in me eschews such delineations in favor of a subjective, flexible understanding to human identities. (My fancy way of saying to you birders out there - I mean all this tongue-in-cheek!). Furthermore, these types tend to blend into one another: for instance, I have dabbled in Listing and Photographing, and will possibly one day graduate to a Retiree-birder (more a fear of impending fate than life ambition).

But before we get to these classic archetypes, let's explore some historic birder varieties (and in the process, imagine THEIR spouses and significant others!)

1. The Augur

In the ancient world - particularly the Roman empire -

these dudes (sorry ladies, this was -100 wave feminism) would study the

behavior of birds to interpret the will of the gods. Different birds

were associated with various omens, some positive and some negative.

Eagles and vultures were popular for flight pattern observations,

whereas owls, crows, ravens, and chickens were important for their

different calls and vocalizations. Seems to me like a religious excuse

for birding, no?

Description: Male, characteristic long robes, high position within society

Geographical Range: Ancient Rome and vicinity

Status: Extinct (except, perhaps at the Renaissance Fair)

2. The Falconer

This individual, easily recognized by the falcon or

hawk perched on his/her shoulder, trains birds of prey to help hunt and

retrieve wild animals. Since ancient Mesopotamia, falconry has been an

art form admired by many and requiring intensive training and skills.

While the practice reached its peak in Europe in the 17th century, some

falconers still exist today and use radio transmitters to keep track of

their birds. Interestingly, in 2010 falconry was added to UNESCO's list

of "intangible cultural heritage." (Birders: 1, Spouses: 0).

Description: Primarily male, bird poop on shoulder.

Geographical Range: All over the ancient and modern world.

Status: Endangered

3. The Pigeon Fancier

Throughout history, people have bred and kept pigeons

for a variety of purposes, from wartime messengers to aerial

competitors to aesthetic fancy. Pigeon Fanciers often build elaborate

pens (see Jim Jarmusch's Ghost Dog) to house their birds. Famous pigeon keepers include Queen Elizabeth II, Nikola Tesla, and Pablo Picasso.

Description: Highly varied, but similarities in housing design to allow for bird flocks.

Geographical Range: Abundant throughout the world going back 10,000 years ago.

Status: Plentiful

4. The Photographer

This birder, easily spotted by the camera lens

jutting out from the face, takes pride in procuring that "perfect shot"

of a variety of birds. Rather than amassing a long list of

never-before-seen birds, the photographer will often spend hours taking

pictures of a single specimen from every possible angle. These folks

often do not play nicely with other birder types, such as The Retiree

animal lover (see below). Spouses of The Photographer can occasionally

be spotted in the background of photos, eclipsed by an eagle wing or hauling a tripod.

Description: Varied, always toting camera with multiple lenses.

Geographical Range: Abundant all over.

Status: Plentiful, especially as camera technology becomes more advanced and equipment cheaper.

5. The Lister

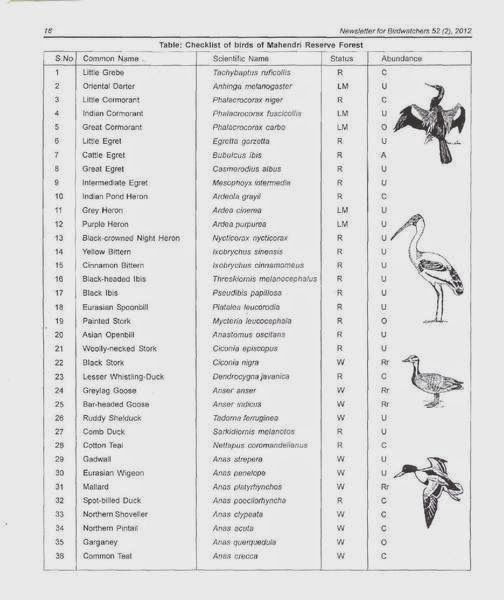

Despite my reluctance to bird, I've realized in recent years that this is the closest I get to a birder. Listers have a sole mission: see every possible bird species in a given area and write them all down. They usually carry around field guides with pages in the back that allow for a tally mark next to each species seen, or alternatively, a checklist from a nearby Visitor Center listing all the birds in a particular national park or forest. Many other birder types, such as The Retiree or The Naturalist, resent The Listers myopic attitude towards bird watching.

Description: Characterized by a field guide or checklist in hand, as well as a pen or pencil. Moves quickly throughout a given area, rather than lingering on individual birds.

Geographical Range: Most abundant in parks, near Ranger's Stations where checklists are available.

Status: Invasive (Shout out to Stacy Rosenbaum).

6. The Retiree (aka Woman in Tennis Shoes)

The Retiree is committed to bird-watching as a hobby

during old age. These men and women often travel in groups of several

individuals, sharing field guides, stories of past birding adventures,

and thoughts on species identification. They usually have little

interest in either photography or scientific investigation, instead

preferring to look at yet another LBJ (Little Brown Job, as birders

refer to the many hard-to-identify small birds) for hours.

Description: Usually female, but not exclusively. Wears tennis shoes and comfortable clothing. Carries binoculars. Has gray hair.

Geographical Range: Abundant all over, but primarily seen in parks with easy accessibility for the elderly.

Status: Plentiful.

7. The Overly Precocious Child

If you encounter this young birder in the field, try

to get away as quickly as possible. The Overly Precocious Child will

lecture you on every bird in the area, with complete disregard to your

interest or background knowledge. Often, though not always, has birder

parent.

Description: Young, wears outdoor/safari gear, verbose.

Geographical Range: Abundant in urban parks and in areas where family vacations are common.

Status: Uncommon, but on the rise.

8. The Twitcher

Twitchers, named after the nervous behavior of 20th

century British birder Howard Medhurst, seek to add as many species to

their lifetime list as humanly possible. This ambition brings them to

far flung places. Importantly, they differ from other birder types in

that they spend very little time with any particular individual bird,

preferring instead to check it off a list and move on. Similar to The

Lister, but with a longer-term goal to see every bird possible during

their lifetime.

Description: Twitchy.

Geographical Range: Abundant in Britain, where bird enthusiasts abound and the term originates.

Status: Plentiful in Britain, scattered elsewhere.

9. The Scientist

Subtype A) The Naturalist-Pacifist

This type of ornithologist is an enthusiastic animal

lover and peaceful bird watcher. Despite the need to collect specimens

for research, The Naturalist will opt to use mist-netting or

catch-and-release wherever possible. These individuals will patiently

view the same bird for hours, regardless of whether it is their first or

hundredth time seeing that particular species, much to the dismay of

non-birding partners.

Description: Dorky safari-style clothes, binoculars, field guides always in hand.

Geographical Range: Abundant all over.

Status: Plentiful.

Subtype B) The Collector-Gun Enthusiast

This guy (or gal, occasionally), is the opposite of

the other Scientist type - an avid gun enthusiast who enjoys hunting in

order to amass specimens for research collections. Often PhD students,

research assistants or museum curatorial staff. (I should note that many collectors view hunting as a necessary evil, rather than a sport.)

Description: Identifiable by hunting rifle with small ammo in order to not damage specimens, camping gear.

Geographical Range: Abundant particularly near museums and research centers.

Status: Plentiful, especially in North America.

Okay, but on a more serious note: what insight might all these different profiles give us on birding, on the types of people it attracts and why? Well, my personal confession is that Listing appeals greatly to the Type A, anxious, over-achiever in me. I'll admit that while I lived in rural South Africa for a year, I got to the point where sometimes I'd drive 2 or 3 miles out of my way to see a nest of herons that I already knew was there, only to check it off my Daily Bird List (a clever way of making sure my Birder-Spouse read my emails!). There was something immensely satisfying about seeing all those little check marks in the back of my field guide, and something incredibly maddening about the empty boxes scattered among them (damn you, elusive Secretary Bird!) In contrast, I've met birders that care little for listing, instead reveling in the gorgeous feather colors that help them achieve that perfect photograph (try googling images for the Banded Pitta or Lilac Breasted Roller and you'll understand). The Naturalist immerses him or herself in the wonders that nature has to offer, while the Collector seems to enjoy the ability to not only watch nature, but perhaps even dominate it. All this is my way of saying that hobbies can be incredibly intriguing in their ability to reveal not just what we do, but what our activities say about who we are. These archetypes give us a potential window into the incredible diversity of what it means to be human, far beyond just those who watch birds. What makes some of us dog people and others squarely in the cat camp? Why do zoos hold such immense appeal for people of all ages worldwide? Anthropologists strive to understand and identify human cultural forms, such as religious rituals, child-rearing practices or kinship relations. How might the various birding subcultures contain within them new ways of examining the human experience and its relationship with the natural world?

Feel free to add more birder types in the Comments section!

In order to properly delve into the topic of birders, we first need to build our birder-watching identification skills. How do you tell the difference between a data-collecting ornithologist and a camera-wielding bird photographer? Can you spot which birder is just there to cross that "lifebird" (a species you've yet to see in your lifetime) off her list and which would stop to observe his hundredth cactus wren? (my own birder falls into the latter category.) Despite the seemingly discrete categories outlined here, the cultural anthropologist in me eschews such delineations in favor of a subjective, flexible understanding to human identities. (My fancy way of saying to you birders out there - I mean all this tongue-in-cheek!). Furthermore, these types tend to blend into one another: for instance, I have dabbled in Listing and Photographing, and will possibly one day graduate to a Retiree-birder (more a fear of impending fate than life ambition).

But before we get to these classic archetypes, let's explore some historic birder varieties (and in the process, imagine THEIR spouses and significant others!)

1. The Augur

|

| (bible-history.com) |

Description: Male, characteristic long robes, high position within society

Geographical Range: Ancient Rome and vicinity

Status: Extinct (except, perhaps at the Renaissance Fair)

2. The Falconer

|

| (Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons) |

Description: Primarily male, bird poop on shoulder.

Geographical Range: All over the ancient and modern world.

Status: Endangered

3. The Pigeon Fancier

|

| (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-W0212-035 / Kaufhold, Reinhard / CC-BY-SA) |

Description: Highly varied, but similarities in housing design to allow for bird flocks.

Geographical Range: Abundant throughout the world going back 10,000 years ago.

Status: Plentiful

* * * * *

And now for a modern look at birding types. See if you recognize any signs in your own birder spouse!4. The Photographer

|

| (Photo by author) |

Description: Varied, always toting camera with multiple lenses.

Geographical Range: Abundant all over.

Status: Plentiful, especially as camera technology becomes more advanced and equipment cheaper.

5. The Lister

|

| (Wikimedia Commons) |

Despite my reluctance to bird, I've realized in recent years that this is the closest I get to a birder. Listers have a sole mission: see every possible bird species in a given area and write them all down. They usually carry around field guides with pages in the back that allow for a tally mark next to each species seen, or alternatively, a checklist from a nearby Visitor Center listing all the birds in a particular national park or forest. Many other birder types, such as The Retiree or The Naturalist, resent The Listers myopic attitude towards bird watching.

Description: Characterized by a field guide or checklist in hand, as well as a pen or pencil. Moves quickly throughout a given area, rather than lingering on individual birds.

Geographical Range: Most abundant in parks, near Ranger's Stations where checklists are available.

Status: Invasive (Shout out to Stacy Rosenbaum).

6. The Retiree (aka Woman in Tennis Shoes)

|

| (Wikimedia Commons) |

Description: Usually female, but not exclusively. Wears tennis shoes and comfortable clothing. Carries binoculars. Has gray hair.

Geographical Range: Abundant all over, but primarily seen in parks with easy accessibility for the elderly.

Status: Plentiful.

7. The Overly Precocious Child

|

| (Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons) |

Description: Young, wears outdoor/safari gear, verbose.

Geographical Range: Abundant in urban parks and in areas where family vacations are common.

Status: Uncommon, but on the rise.

8. The Twitcher

|

| (Bird Blind, Photo by Mick Garrett) |

Description: Twitchy.

Geographical Range: Abundant in Britain, where bird enthusiasts abound and the term originates.

Status: Plentiful in Britain, scattered elsewhere.

9. The Scientist

Subtype A) The Naturalist-Pacifist

|

| (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1986-0912-310 / CC-BY-SA) |

Description: Dorky safari-style clothes, binoculars, field guides always in hand.

Geographical Range: Abundant all over.

Status: Plentiful.

Subtype B) The Collector-Gun Enthusiast

|

(Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons) |

Description: Identifiable by hunting rifle with small ammo in order to not damage specimens, camping gear.

Geographical Range: Abundant particularly near museums and research centers.

Status: Plentiful, especially in North America.

Okay, but on a more serious note: what insight might all these different profiles give us on birding, on the types of people it attracts and why? Well, my personal confession is that Listing appeals greatly to the Type A, anxious, over-achiever in me. I'll admit that while I lived in rural South Africa for a year, I got to the point where sometimes I'd drive 2 or 3 miles out of my way to see a nest of herons that I already knew was there, only to check it off my Daily Bird List (a clever way of making sure my Birder-Spouse read my emails!). There was something immensely satisfying about seeing all those little check marks in the back of my field guide, and something incredibly maddening about the empty boxes scattered among them (damn you, elusive Secretary Bird!) In contrast, I've met birders that care little for listing, instead reveling in the gorgeous feather colors that help them achieve that perfect photograph (try googling images for the Banded Pitta or Lilac Breasted Roller and you'll understand). The Naturalist immerses him or herself in the wonders that nature has to offer, while the Collector seems to enjoy the ability to not only watch nature, but perhaps even dominate it. All this is my way of saying that hobbies can be incredibly intriguing in their ability to reveal not just what we do, but what our activities say about who we are. These archetypes give us a potential window into the incredible diversity of what it means to be human, far beyond just those who watch birds. What makes some of us dog people and others squarely in the cat camp? Why do zoos hold such immense appeal for people of all ages worldwide? Anthropologists strive to understand and identify human cultural forms, such as religious rituals, child-rearing practices or kinship relations. How might the various birding subcultures contain within them new ways of examining the human experience and its relationship with the natural world?

Feel free to add more birder types in the Comments section!

Thursday, June 5, 2014

A Reluctant Start

As the significant other of an avid birder for the past 6 years, I have noticed a slow but steady change in the world around me. Formerly quiet, peaceful tree-lined streets suddenly burst with a cacophony of chirping warblers in the early weeks of spring. Floor to ceiling windows, once lovely features of modernist home design, have become death traps waiting silently to break the necks of poor, unsuspecting woodpeckers. Trips to the beach are as much about tan lines as they are about the exciting possibility of spotting an oystercatcher digging in the sand for its prey.

I'm an anthropologist. I study humans. Though I've always loved the non-human variety of animals, I decided long ago that my contribution to the world had to revolve around ameliorating the many ills of modern societies. With so much suffering everywhere, why would anyone invest their time in figuring out the phylogenetic relationship between different species of geckos or the biomass of all the beetles in the rainforest? And yet, as you can probably already tell by my use of the world "reluctant" in this blog title (note that it isn't "The Spiteful Birder" or "The Non-Birder" - though it likely would have been had I started this a few years earlier), my relationship with a birder has most certainly changed my outlook on non-human creatures and all the scientific queries that are associated with them.

On a more pragmatic note, it's pretty hard to marry a birder if you aren't willing to pick up a pair of binoculars once in awhile. Oh, what we sacrifice for love - in my case, it has been sleeping past 6AM on vacations and hiking at any kind of reasonable pace.

Therefore, this blog isn't going to be about birding (in fact, my pact to you, dear reader, is that a photo of a bird will never grace this site with its presence) but instead about all the human entanglements with birds and their watchers. For those anthropologists among you, consider this a place to ethnographically explore birders through a digital binocular - it's high time somebody put THEM in front of the lens, isn't it? For those fellow spouses of birders, consider this a self-help group of sorts. And for the rest of you, perhaps this blog will either inspire you to get out there and look at some birds or to resolutely declare yourself a non-birder for life.

Our bookshelf (I never said there wouldn't be DRAWINGS of birds or photos of photos of birds.)

Next up...the field guide to birders. Stay tuned.

I'm an anthropologist. I study humans. Though I've always loved the non-human variety of animals, I decided long ago that my contribution to the world had to revolve around ameliorating the many ills of modern societies. With so much suffering everywhere, why would anyone invest their time in figuring out the phylogenetic relationship between different species of geckos or the biomass of all the beetles in the rainforest? And yet, as you can probably already tell by my use of the world "reluctant" in this blog title (note that it isn't "The Spiteful Birder" or "The Non-Birder" - though it likely would have been had I started this a few years earlier), my relationship with a birder has most certainly changed my outlook on non-human creatures and all the scientific queries that are associated with them.

On a more pragmatic note, it's pretty hard to marry a birder if you aren't willing to pick up a pair of binoculars once in awhile. Oh, what we sacrifice for love - in my case, it has been sleeping past 6AM on vacations and hiking at any kind of reasonable pace.

Therefore, this blog isn't going to be about birding (in fact, my pact to you, dear reader, is that a photo of a bird will never grace this site with its presence) but instead about all the human entanglements with birds and their watchers. For those anthropologists among you, consider this a place to ethnographically explore birders through a digital binocular - it's high time somebody put THEM in front of the lens, isn't it? For those fellow spouses of birders, consider this a self-help group of sorts. And for the rest of you, perhaps this blog will either inspire you to get out there and look at some birds or to resolutely declare yourself a non-birder for life.

Our bookshelf (I never said there wouldn't be DRAWINGS of birds or photos of photos of birds.)

Next up...the field guide to birders. Stay tuned.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)